Keri-Lee and I are now the East IDL team.

IDL? you ask.

Take your pick: idol, idyll, idle, or, the correct answer: Information & Digital Literacies.

It's a tag I am more comfortable with than "21st century" (no matter what you put after it, whether "skills" or "learning" or "tools") -- because, as Dennis Harter points out, we're already in the 21st century and will be for the rest of our lives, and the adjective "21st century" (like "Web 2.0") may have instant recognition to those in the educational blogosphere, but induces either alienation or only vague comprehension in others.

It's understandable to want to stress the new and to avoid focusing on technology alone, but I'm voting for a return to Information and Digital Literacies as the label for what we are trying to spread and embed in the classrooms, which I think David Warlick captures in these statements:

"As I say again and again, it is not the computers that are impacting us as a society or as individuals. It’s what we can do with information that is changing things." (2008)

"... embracing tools that give all their student-learners and teacher-learners ubiquitous access to networked, digital, and abundant information — and the capacity to work that information and express discoveries and outcomes compellingly to authentic audiences." (2009)Information & Digital Lite

racies also nicely combines the main characteristic of our respective subject areas -- me as the Teacher-Librarian and Keri-Lee as the ICT Facilitator.

racies also nicely combines the main characteristic of our respective subject areas -- me as the Teacher-Librarian and Keri-Lee as the ICT Facilitator.What's new this year besides recognition of us as a team?

One, Keri-Lee is no longer an ICT "teacher" on a release-time, weekly fixed schedule with classes; instead she's a facilitator on a flexi-schedule, collaborating with classroom teachers on different units of inquiry, as I have been.

Two, we're using the ISTE NETS for Students as our roadmap and are working on a document for our teachers, translating the NETS Profiles into possible experiences/scenarios for our students based on our curriculum and taking the IBO PYP Transdisciplinary Skills (Communication, Research, Thinking, Self-Management, and Social) into account. In addition, we're looking at the NETS for Teachers, Administrators, and Technology Facilitators.

Three, we have some new technology toys, which teachers can book, just like they can book us: a set of iPod Touches and a set of video cameras.

In celebration of this shift, Keri-Lee and I attended the 21st Century Learning @ Hong Kong: Extending Tomorrow's Leaders with Digital Learning, held September 17-19, 2009, at Hong Kong International School (HKIS).

In celebration of this shift, Keri-Lee and I attended the 21st Century Learning @ Hong Kong: Extending Tomorrow's Leaders with Digital Learning, held September 17-19, 2009, at Hong Kong International School (HKIS).With over 500 attendees, many of us from overseas, there was a good mix of teachers (a lot of IT/ICT, but also librarians and others) - and the program had plenty to offer.

(NB: I presented a workshop with Beth Gourley, from the International School of Tianjin, called Digital Gist: Harnessing digital content for learning and the library: an inquiry into texts online in audio, video, and e-book formats.)

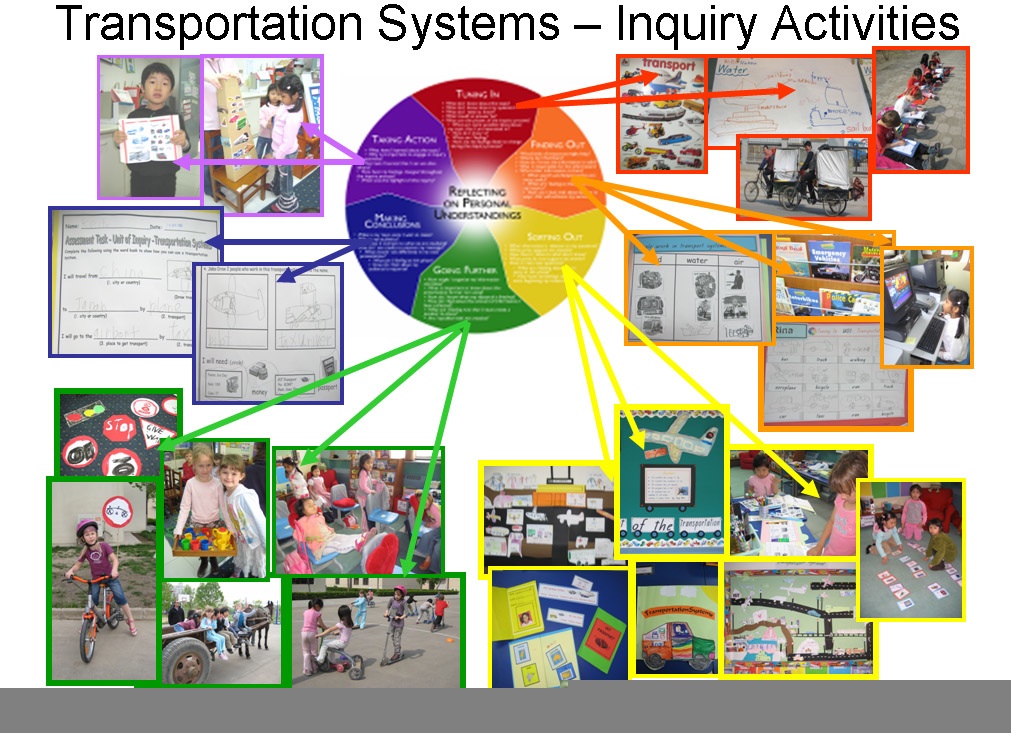

(NB: I presented a workshop with Beth Gourley, from the International School of Tianjin, called Digital Gist: Harnessing digital content for learning and the library: an inquiry into texts online in audio, video, and e-book formats.)One of the most useful sessions Keri-Lee and I attended, in terms of our goals for our own school, was Walking the Talk: 21st Century Learning in Curriculum Design and Learning by Greg Curtis, Curriculum Director at the International School of Beijing (ISB).

He started off with this video (from The Onion) re the "21st century skills" our kids are going to need.

Greg stressed that the 21st century movement (yes, they do use the term at ISB) is a learning one, not a technology one -- and therefore needs to be driven by the curriculum unit, not the IT department -- that it's about strategic planning and future visioning, not IT planning. (Read: management buy-in is critical.)

At ISB they are trying to create a "pull" culture, rather than a "push" one -- to infuse technology into learning experiences and explorations, not force it. A culture where technology is expected to be used and will be drawn in. Never technology for its own sake. Context is everything. It's all about the learning -- always about the learning.

He walked us through ISB's Lea

rning 21 framework -- with Standards in the center, then moving out a ring to the Learning 21 Approaches, and then the outer ring of Learning 21 Skills. (I was pleased to learn they had blended the library and technology standards.)

rning 21 framework -- with Standards in the center, then moving out a ring to the Learning 21 Approaches, and then the outer ring of Learning 21 Skills. (I was pleased to learn they had blended the library and technology standards.)All these are incorporated, along with Understanding by Design constructs, into their Curriculum Mapping system, which allows them to visually check the spread of assessment tasks and see how the Learn 21 Approaches and Skills are being integrated.

To implement this program, ISB has initiated an early release afternoon on Wednesdays, providing two hours a week of concentrated staff professional development time.

What a tremendous commitment to a program and a process. I look forward to following ISB's progress over the next few years.

See Greg's handout - scanned and uploaded to Google Docs

See also my rough notes on his presentation - in Google Docs

(By the way, I was pleased to see Sharon Vipond, the secondary librarian at HKIS, has posted her notes on all the keynote speeches from the conference.)

It was such a beneficial and collaborative exercise attending the conference together with Keri-Lee -- we were continually bouncing impressions and ideas off each other. We'll see how we get on with our own integrated standards, approaches, and skills initiative -- and our efforts to infuse information and digital literacy into our East campus classrooms.

And hats off to the conference organizers -- it was a well-executed event and I would definitely attend it again.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=c83c143b-8a9a-40ff-9497-1d88f3aaa5fa)