Clay doesn't stop. Luckily the blog entry he just wrote -- “You Suck at Photoshop”: Paragon of Creative Project-Based Learning -- fits in perfectly with where I want to continue from my last post (which was spurred by a previous post of his: Barbarians with Laptops).

It's about the importance of narrative in the teaching/learning process.

Okay, You Suck at Photoshop isn't "a grand narrative" (one of the three essential elements of teaching according to Michael Wesch (see my previous post)). But the format could be used to help convey one, incorporating "disciplinary knowledge" into a funny story with a good hook. And Clay showed us an example of a teacher, Lynn Hunt of UCLA -- a "sage on the stage" -- presenting a compelling introduction to the Enlightenment -- by telling us a good story. It's "chalk and talk" but effective. (See his blog post: New Tech Teaching Habits.)

The power of storytelling is often lost in the ongoing debates over:

- teacher-centered vs. student-centered learning

- content vs. process focus

- traditional vs. progressive

- "sage on the stage" vs. "guide on the side"

- disciplinary knowledge vs. 21st century skills

- Kieran Egan's 2009 book, The Future of Education - as well as Learning in Depth: A simple innovation that can transform schooling, due out from the University of Chicago Press in 2010;

- Roger Schank's upcoming book, Cognition! Teaching Kids to Think (see the first four chapters he's made available on his website)

Roger Schank

The best historical introduction to Roger Schank is probably via the Edge.org website. You might read his article "Information is Surprises" (1995). Especially note the comments by other people at the end -- re him, not that article. I particularly like this one:

W. Daniel Hillis: The Roger Schank I knew was a thorn in everybody's side — constructively so. The interesting thing about Roger Schank, something he shares with Minsky, is the fact that he's produced an incredible string of students. Anybody who's produced such a great string of students has to be a constructive pain in the ass. He's always taken an adversarial stance in his theories. He doesn't just say, "Here's my theory." He says, "Here's why I'm right and everybody else is an idiot." He's often right.Okay, now that you're primed for someone quite opinionated (I like that phrase: "a constructive pain the ass"...), go watch this Jan 2009 video, filmed in Barcelona where he is helping to open a new Institute for the Learning Sciences (as part of their Business Engineering program*) -- based on a Story-Centered Curriculum. He goes through everything wrong with existing schools and describes his ideal school:

In summary: "Every curriculum should tell a story... and the story should be one that tells what the life of the future practitioner is like (and it should involve lots of practice)." As he says, teaching doesn't mean talking -- people aren't good at listening -- we listen to be entertained, not to learn. Learning happens as a result of being hooked by good stories -- and by practicing goal-based scenarios that are fun or obviously useful.

Here are my notes on Roger Schank's 1999 book, Tell Me a Story: Narrative and Intelligence, a thought-provoking read for teacher-librarians as it's about stories, learning, and information retrieval (out of the brain, not the internet) --and so relates to fiction, non-fiction, and tagging/cataloging. (Google Books makes a lot of the book available online, as well as the foreword by the literary critic Gary Saul Morson.)

Teaching is the right story at the right time.

Good stories with lots of information allow listeners to derive their own conclusions.

We do not remember a whole story, but only the gist, indexed in different ways.

Listening is hard -- stories usually just trigger stories back and forth -- how does new learning occur?

Creativity is the adaptation of old stories to new purposes -- it arises not from the void, but from the drawer. And the drawer is only full by virtue of intelligent indexing over time -- the collecting of lots of stories in the brain. Understanding is the process of index extraction -- figuring out what story to tell.

Find an anomaly -- ask a question -- get a story. Anomalies are when we don't know the answer. When we have no story to tell, we look for one -- by asking ourselves questions.

Curiosity is about recognizing anomalies and having the ability to take pleasure in exploring them, which leads us to the value of the search process itself and to prefer answers that lead to ever more questions.

Or as Schank says on page 231: "Learning to explain phenomena such that one continues to be fascinated by the failure of one's explanations creates a continuing cycle of thinking that is the crux of intelligence."

Or as Schank says on page 231: "Learning to explain phenomena such that one continues to be fascinated by the failure of one's explanations creates a continuing cycle of thinking that is the crux of intelligence."Re the failure to listen to failure, see this recent Wired article - Accept Defeat: The Neuroscience of Screwing Up. The importance of having a broad input of stories -- and a broad audience -- is highlighted:

When Dunbar reviewed the transcripts of the meeting, he found that the intellectual mix generated a distinct type of interaction in which the scientists were forced to rely on metaphors and analogies to express themselves. (That’s because, unlike the E. coli group, the second lab lacked a specialized language that everyone could understand.) These abstractions proved essential for problem-solving, as they encouraged the scientists to reconsider their assumptions. Having to explain the problem to someone else forced them to think, if only for a moment, like an intellectual on the margins, filled with self-skepticism.This is similar to something a former PhD student said about what he learned from Schank (quoted by Schank in his four-chapter preview of his upcoming book:

[bold added]

You taught me that often our theories get so complex that it takes a specialist with years of training to understand them. When we get our theories this distant from everyday life and everyday people, it is awkward explaining what we do when in conversation with our family, friends, the press, and even upper level executives, etc. You taught me to test to see if what you are doing matters and is of interest to the everyday person seeking distraction and some entertainment, but not entirely brain dead, with some curiosity left about life and what others think.In other words, can you make an interesting story out of it?

Kieran Egan

Kieran Egan argues that students have access to plenty of information - the problem is getting it into them and getting it to mean anything to them. Knowledge exists only in people, in living tissue in our bodies; what exists in libraries and computers are only codes or externally stored symbolic material.

Kieran Egan argues that students have access to plenty of information - the problem is getting it into them and getting it to mean anything to them. Knowledge exists only in people, in living tissue in our bodies; what exists in libraries and computers are only codes or externally stored symbolic material.Egan insists that students' imaginations can only work with what they know, so a great deal of content knowledge is required. He's an advocate of students becoming experts, e.g., by studying one topic throughout their whole school career (in addition to the usual curriculum). (See his new Learning in Depth project.)

Storytelling fits into Egan's larger framework of cognitive tools and theory of Imaginative Education. These cognitive tools are the things that enable our brains to do cultural work -- and he likens to operating systems or programs in the brain, forms of which are running at all times in varying degrees at all ages: the Somatic (the body & its senses), the Mythic (oral language), the Romantic (reading and writing), the Philosophic (the meta-narrative of systems in the world), and the Ironic (multiple perspectives in the mind at one time).

For more details on Egan's framework, see The Educated Mind: how cognitive tools shape our understanding (1997); for a more practical guide to his storytelling ideas for younger students, see his Teaching as Storytelling: an alternative approach to teaching and curriculum in the elementary school (1986).

Egan defines education as "the process in which we maximize the tool kit we individually take from the external storehouse of culture." For me, libraries (whether physical or virtual) are primary portals to that cultural storehouse. (As they say, knowledge is free at the library -- bring your own container.) And librarians are there with embodied knowledge to help people find the right story at the right time.

More on Storytelling and Metaphors

- Vivian Gussin Paley and her books are all about storytelling with young children -- and how story and play are inextricable in the learning process (which will be the topic of my next post -- stories, serious play and disciplinary knowledge)

- TED talks that exemplify a great story: Sherwin Nuland on electroshock therapy and Jill Bolte Taylor's stroke of insight -- and a TED talk that gives a great example of being taught how to tell a story at a young age: Doris Kearns Goodwin

- Randy Pausch's Last Lecture: on achieving your childhood dreams

- PostSecret - each postcard is the tip of an iceberg of a story - (I can't help but think some were created as an exercise by a budding novelist...)

- The Moth podcasts -- true stories told live on stage with no notes or props

- Two connected books: Exercises in Style (1947) by Raymond Queneau, and its modern counterpart: 99 Ways to Tell a Story (2005) by Matt Madden

- TED talk: James Geary, metaphorically speaking

- George Lakoff is the expert on metaphors as far as I'm concerned - his Metaphors We Live By (1980) (co-authored with Mark Johnson) is the place to start, but don't stop there....

- Speaking of metaphors, I can't help but throw in Stephen Colbert and Sean Penn on April 19, 2007 competing in the Meta-Free-Phor-All: Shall I Nail Thee to a Summer's Day?

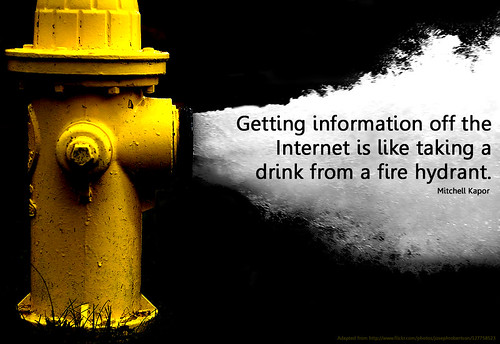

The Colbert Report Mon - Thurs 11:30pm / 10:30c Meta-Free-Phor-All: Shall I Nail Thee to a Summer's Day? Colbert Report Full Episodes Political Humor Economy - Last but not least, the metaphor I use to introduce information overload and the need for smart searching on the internet:

Image via Will Lion on Flickr

* re business schools, there's a debate in the NYTimes re the appropriate metaphor for how universities (especially business schools) treat students - as customers? as products? For a really unusual business school - one that is living 21st century skills, check out KaosPilot.

And for an example of graduate schools looking for applicants with creative storytelling capabilities -- or at least competency in metaphors, see this NYTimes slideshow of images meant to prompt applicants' admission essays: What Do You See?