"We have a responsibility to introduce children to things they don't yet know they will love." -- Edith Ackermann

came onto my radar this summer. (See

my previous blog post on "Constructing Modern Knowledge 2014"

for the context.)

Such a charming, thoughtful expert on play and learning. And

-- she worked with Jean Piaget and Seymour Papert, and has been associated with MIT for years (as well as other universities).

She loves

,

,

, and

. A true educational radical (or realist) -- depending on where you stand.

Read this recent interview with her on creativity, talent, and intuition

-- in a journal aimed at architects.

I wish I could find her CMK14 slides online. I took basic shots into my Penultimate notes, but they aren't good enough to reproduce, e.g.,

The part of her talk that interested me the most was her description of

the iterative cycle of self-learning

, which she outlined as:

Connect -- Wow! I can't believe... -- the inspiration - the imaginarium

Construct -- hands-on -- the atelier -- immersion and innovation

Contemplate -- heads-in -- mindfulness -- the sanctuary or secret garden

Cast -- play-back -- re-visit -- stage -- dramatize -- experiment

Con-vivire -- the sharing -- the piazza -- the agora -- expressivity

She stressed these are just guidelines for what happens along the way in different ways -- that the stages should never be used prescriptively.

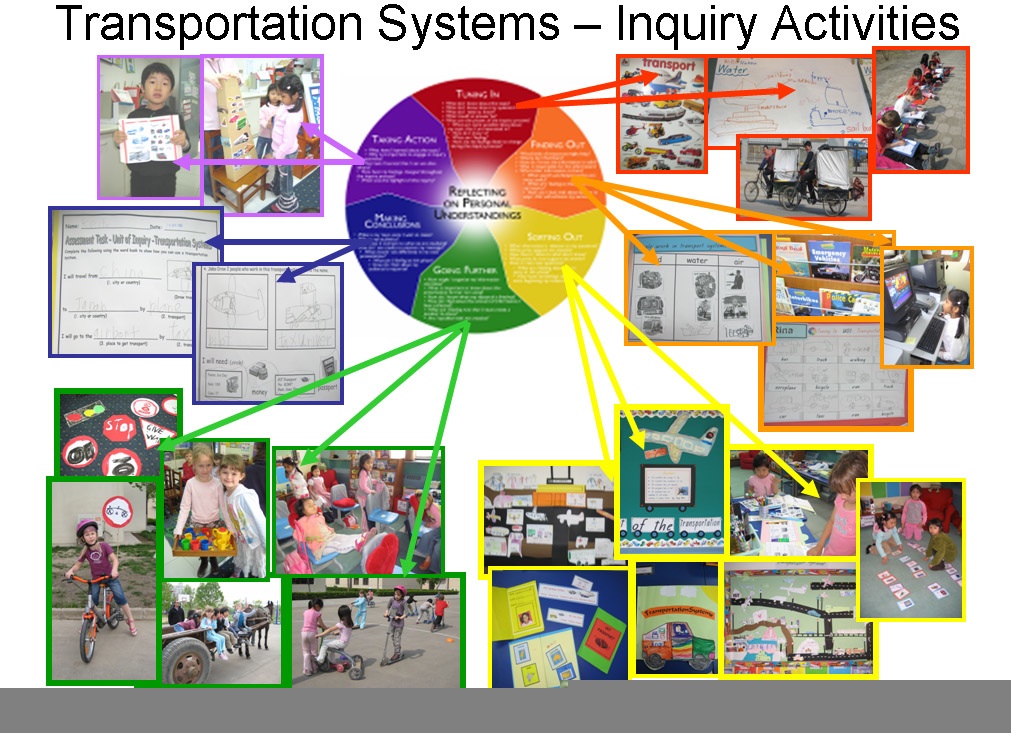

Our school is just settling on some common terminology around

a research model

-- one that will be differentiated for Infant (K1 to Grade 1), Junior (Grade 2 to Grade 5), Middle School (Grade 6 to Grade 8) and High School (Grade 9 to Grade 12).

A midway meeting ground has been agreed, e.g., here is a standard arising out of the articulation of the middle school curriculum:

The blog "What Ed Said" (Edna Sackson) recently had a post

on her frustration with expected slavish commitment to an inquiry cycle model. I agree. You might as well insist everyone follow the same sequence for falling in love or grieving over death. It's useful to appreciate typical stages, but impossible to expect everyone to adhere to them. NB: Kath Murdoch, referenced by Edna, is a frequent professional visitor to our school, and

were key inputs to our process -- see here:

Edith was talking about

Play

-- and undoubtedly about

Inquiry

. But our school is talking about

Research

. Are they all the same thing? Just at different age levels? We'd like to think so.

Research, for middle/high school students, is just a game with adult rules (e.g., alluding to the ideas of others in a constructive and respectful way) -- and our job is to alert them to those rules and to convince them it's a game worth learning (after all, research is a form of adult fun, yes?). As Edith put it, students must learn to add value in the process of borrowing. They must become adept at massaging ideas until they are their own, rather than just functioning as an information broker, passing on ideas. To ride others' ideas until they can feel in solo mode, not fusion mode.

I particularly like Edith's "Cast" phase, with its implicit theatrical connotation. Something between our "Reflect" and "Communicate." It's the part that implies the iterative nature of the process. That you, within your own mind or in the presence of others, re-think what you have, try it out, and ask if it's sufficient, if it's enough.

(I'm also partial to Design Thinking as a basic research model; see my previous blog post:

Carol Kuhlthau Meets Tim Brown

. )

Other things Edith commented upon....

re MOOCs and online learning:

the double standard: it's the new entrepreneurial elite, who are educated onsite with constructivist methods, who are promoting education online where "others" struggle alone;

re today's learners:

growing older younger, and staying younger older;

the tension between temp and "forever" work

the tension between professional mobility and lack of security;

re the role of the eye and the senses:

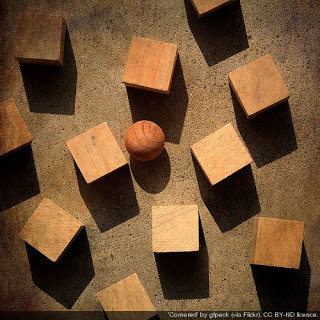

away from Piaget (the rationalist) to Papert (feeling the materials);

the real practitioners (e.g., architects) are always tricking people to get a different perspective;

to crawl out of the old ways of thinking;

tricks to get us off our own beaten path;

using objects creates resistance;

"Learning is all about moving in and out of focus, shifting perspective, and coming to 'see anew.'" -- Edith Ackermann

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=c83c143b-8a9a-40ff-9497-1d88f3aaa5fa)