This piece was originally published on the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative blog — and is cross-posted here.

Collections of global literature for young people can be found all over Singapore — in the libraries of the 50+ international schools that serve the expatriate population of the city-state.

Singapore is a privileged “bubble” in Southeast Asia in so many ways (economically, culturally, educationally, etc.) — and international schools are a bubble within that bubble, given that Singaporeans are not allowed to attend them without special dispensation from the government, which prefers to educate their own citizens but needs attractive schooling options for the elite foreign workforce being enticed to relocate there. (Out of a population of 5.64m in 2018, 3.99m are citizens or permanent residents, while 1.64m are non-resident or expatriate — roughly 30%.)

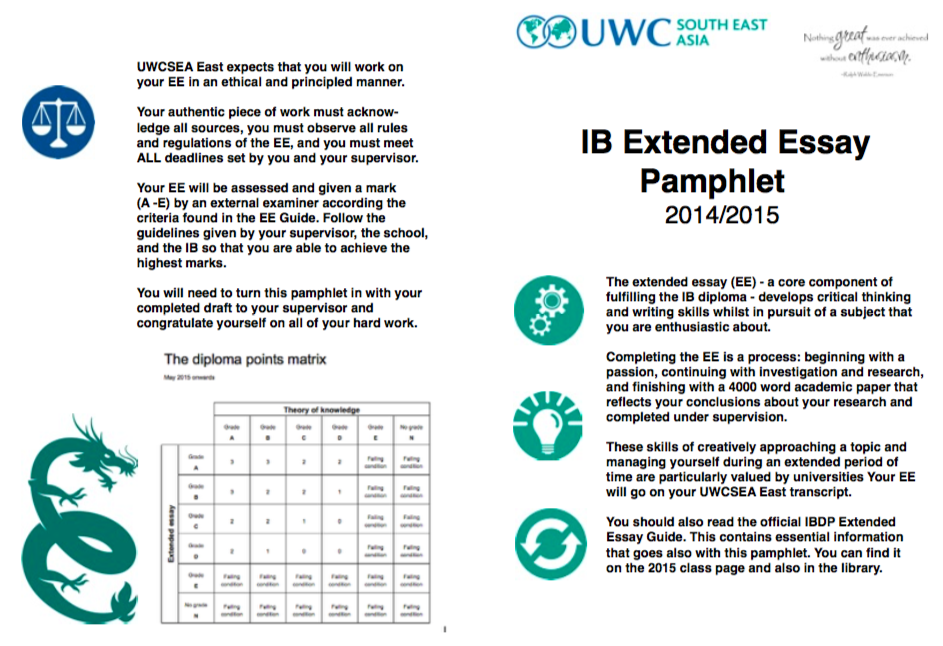

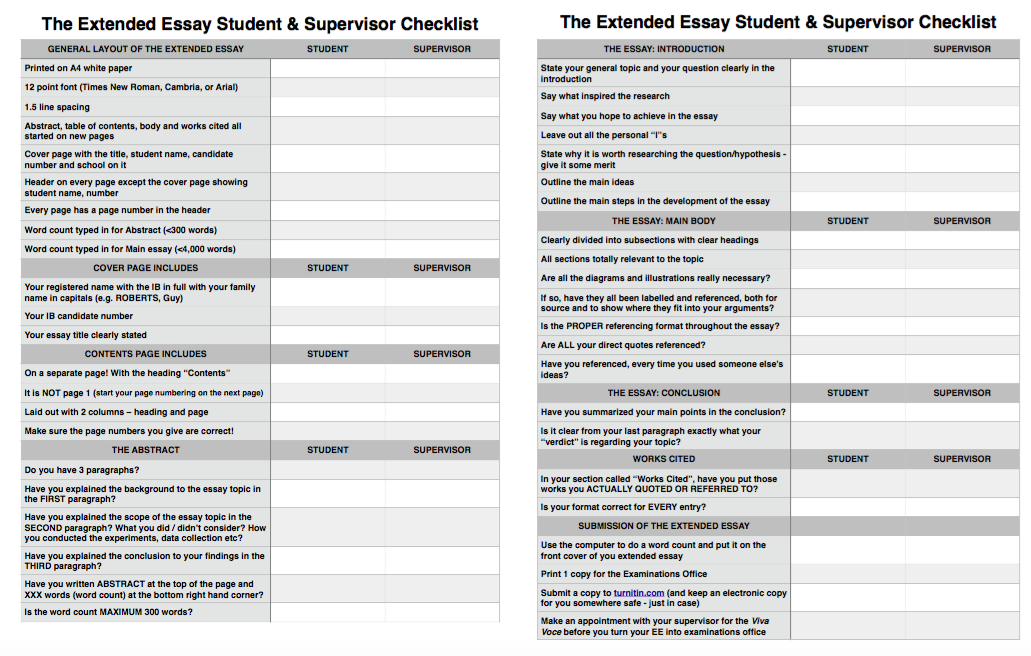

The teacher-librarians in the international schools (which offer national curricula and/or International Baccalaureate programmes -- PYP, MYP, & DP), are a highly connected professional group via ISLN (the International Schools Library Network) — and they represent a good mix of nationalities themselves, as well as expat experiences.

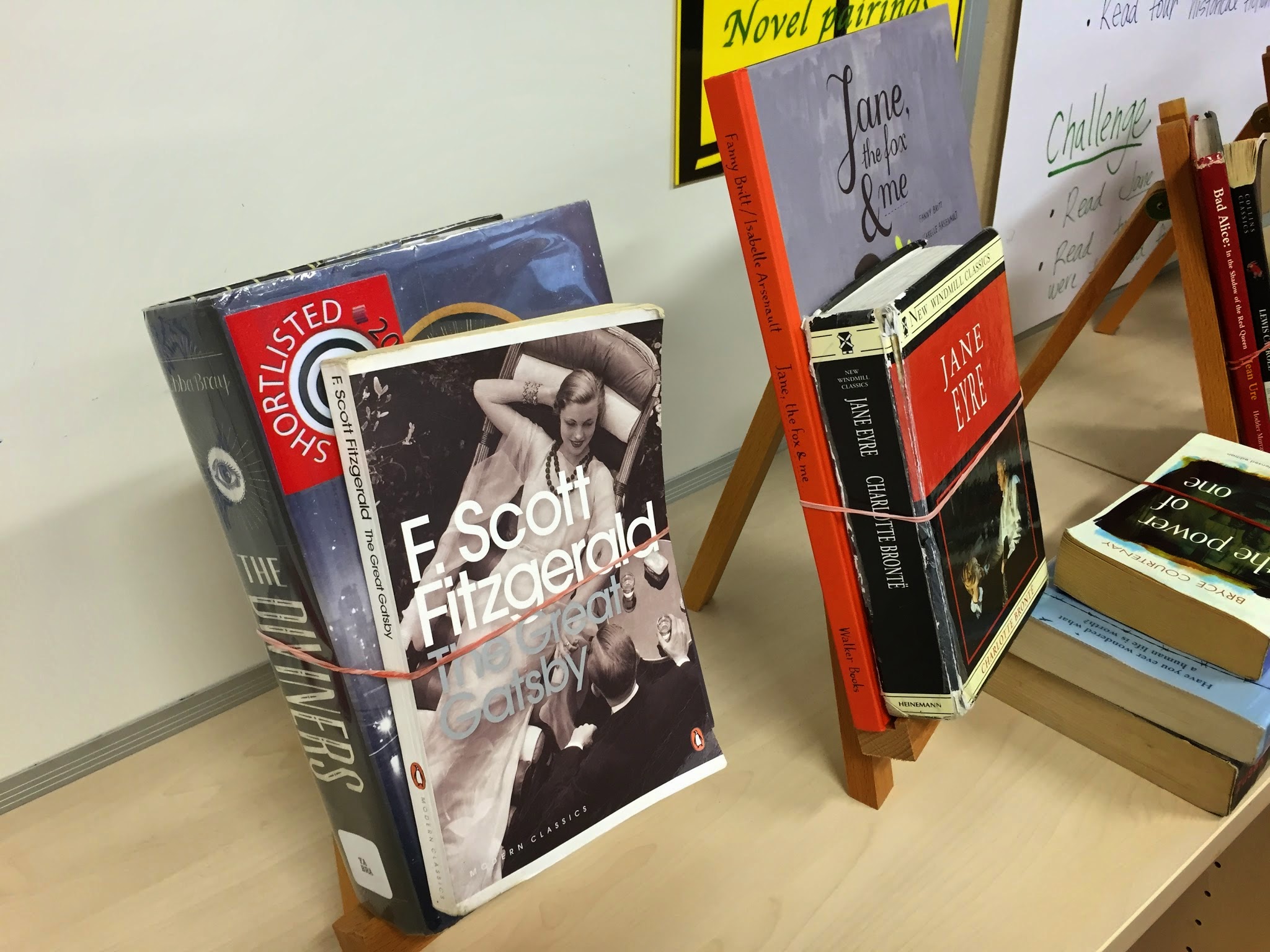

Ten years ago ISLN started the Red Dot book awards — shortlists of recently published books from around the world worth promoting in their schools -- which means books worth buying multiple copies of and worth readers discussing. It was modeled on similar awards run by similar teacher-librarian networks in other countries (e.g., the Panda Awards in China and the Sakura Medal in Japan).

NB: "Red dot" is a proud epithet in Singapore, appropriated from a disparaging comment made years ago by the leader of a neighboring country. The island may be just a little red dot on the map, but the 54-year-old nation now exudes power and potential.

For the Red Dot book awards, eight titles (published or translated within the past four years) are selected in four age categories and students are encouraged to read as many as possible and then to vote for their favorite, with category winners announced for each school and for Singapore as a whole. The voting is just for fun -- there is no prize for the winning titles or authors. The real prize is the students actually reading the shortlists. (You can browse ten years of the book selections by clicking through the slideshows below.)

Early Years -- all shortlists -- on Goodreads

Younger Readers -- all shortlists -- on Goodreads

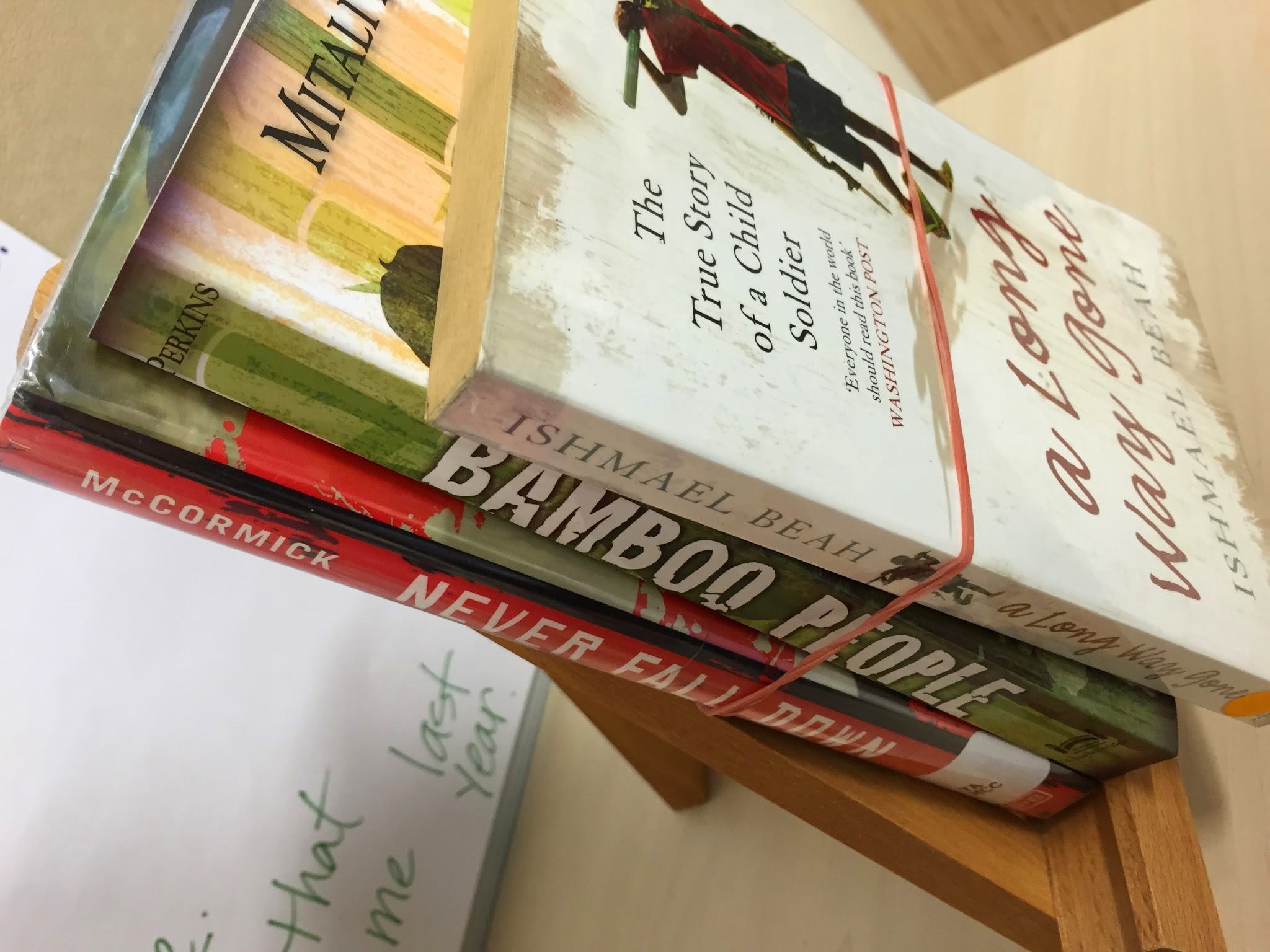

Older Readers -- all shortlists -- on Goodreads

Mature Readers -- all shortlists -- on Goodreads

For the ISLN teacher-librarians who participate in this annual exercise, the personal reward is found in the group process of choosing titles for the shortlists. I've blogged before about the evolution of the award -- and about the wide reading we go through looking for the right ingredients to make up a balanced basket of offerings, always discovering books we love, even if they don't make the shortlist.

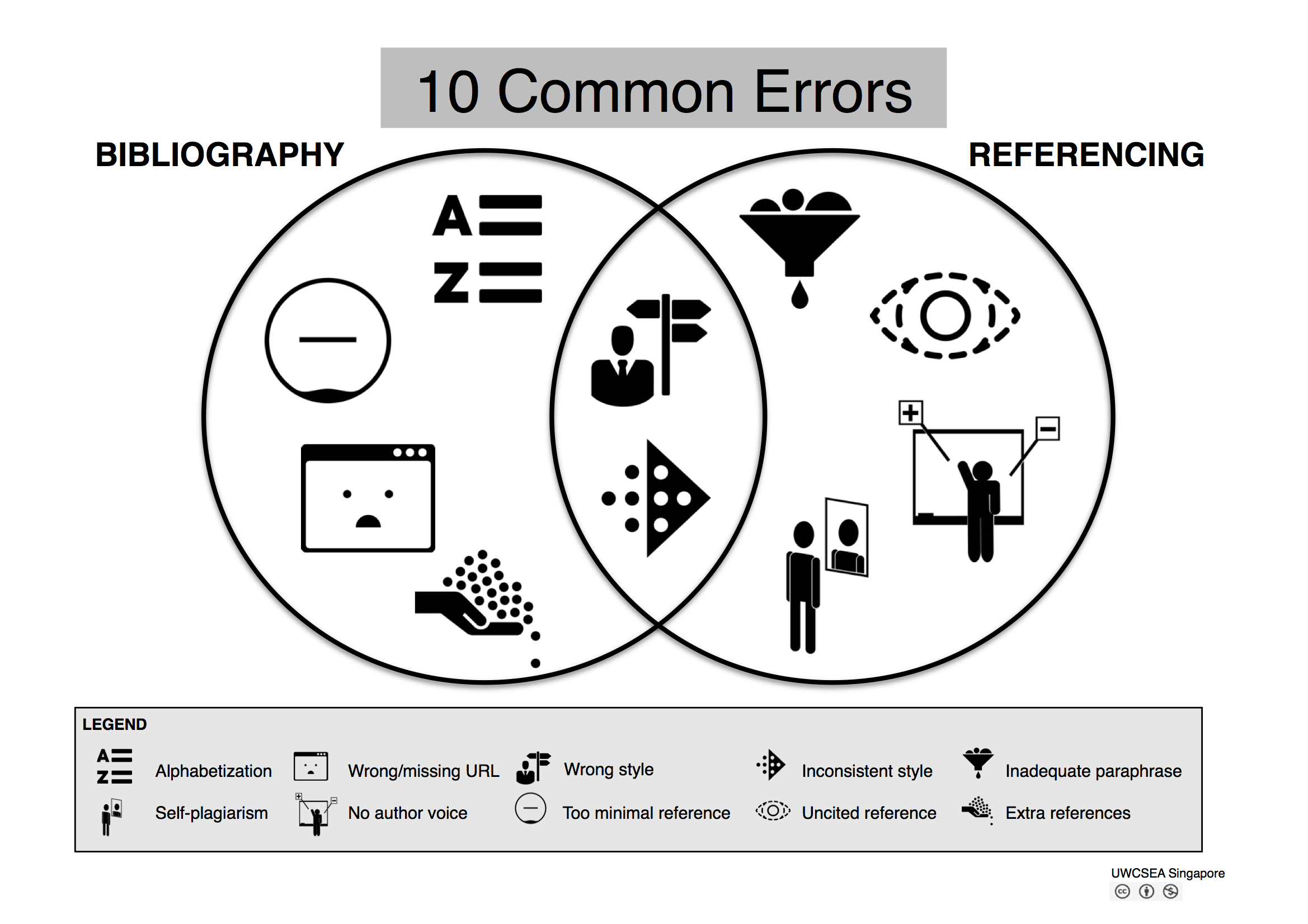

I've also written about the difficulty in ensuring the diversity of our shortlists, remembering diversity is relative. So many of the lists of "best diverse books" for children are not very diverse from an international point of view. Nadine Bailey (another former ISLN member, now working in Beijing) calls it the #NotOurDiversity problem. She speaks for all of us international school teacher-librarians in lamenting the lack of "mirrors" for our third-culture kids and diaspora clientele.

(Have we made mistakes? Yes, I cringe as I see the picture book version of "Three Cups of Tea" by Greg Mortenson on the first year's list -- as he is now known for his "Three Cups of Deceit.")

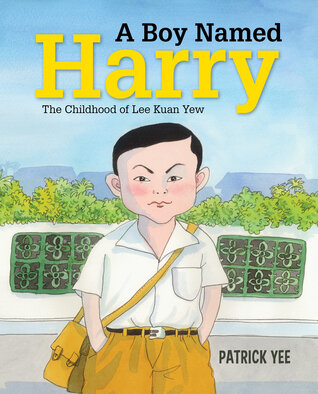

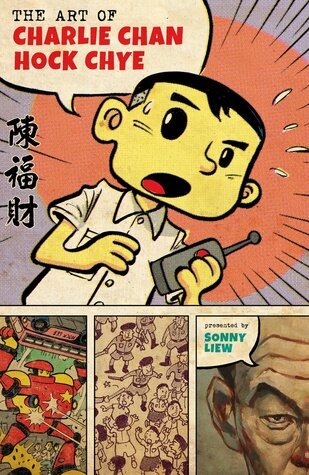

Ideally Singapore books would be included every year, but it doesn't always happen, given the fact that the baskets need to balance not only geographically but also in terms of genre, theme, setting, style, etc. This list in Goodreads shows the ones that have made the shortlists, including "Secrets of Singapore," a fascinating compendium of information by a mother/daughter team; a picture book biography of the founding father of Singapore ("A Boy Named Harry: The Childhood of Lee Kuan Yew"); and the superlative faux history about an artist growing up in Malaya/Singapore, "The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye" by a Malaysian graphic artist.

Books relating to the region are also highly desirable, e.g., "Earth Dragon, Fire Hare," a middle school novel by a New Zealand author about Malaya in 1948 featuring a Kiwi soldier and a Chinese Malay freedom fighter; "Tall Story," a (literally) fantastic story straddling the Philippines and the UK; and a gripping non-fiction account of the 2018 Thai cave rescue, "Rising Water."

Translations are the most important kind of “diversity” or “disruption” needed for the Anglo-centric collections in our schools. As Tiffany Tsao put it, 'power carves the channels that determine how Culture with a capital C flows among countries and their inhabitants.’ And the residual power of the historical British and American empires in Asia is evident in countries like Singapore (though it theoretically recognizes three other official languages — Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil).

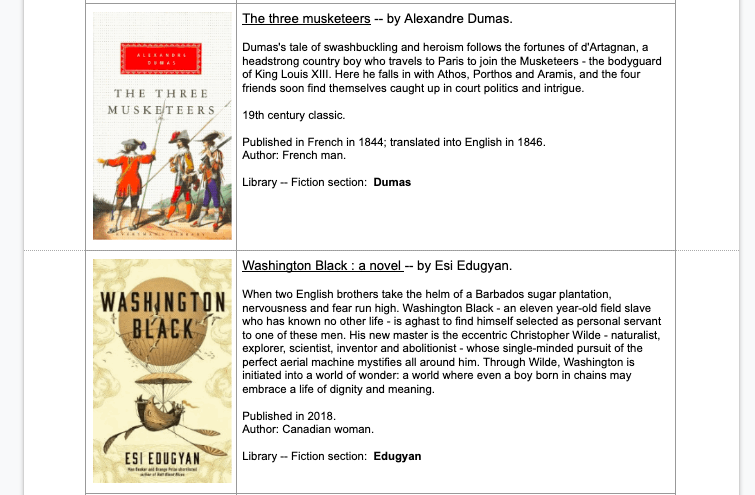

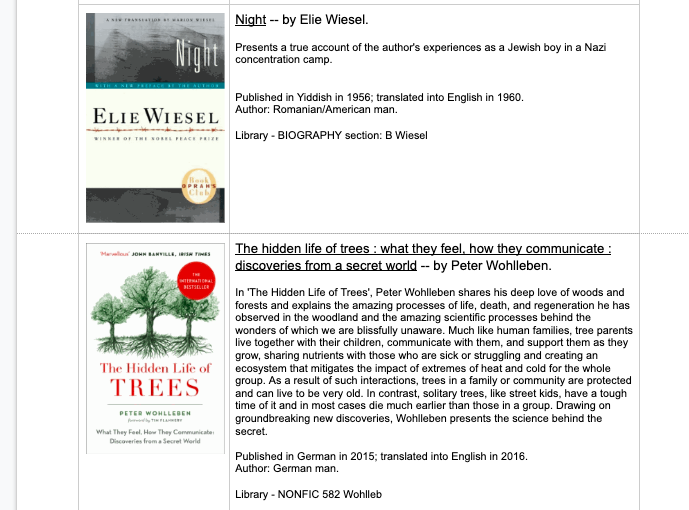

We always welcome works in translations, as evidenced by these past Red Dot choices.

That's why this Global Literature in Libraries Initiative is so valuable, highlighting authors and works in different languages for us to read. I particularly appreciate their LibraryThing catalog of children's and YA literature (originals and translations) for Chinese, Japanese, Korean, German, Polish, and Spanish (so far).

Having said that, IBBY (the International Board on Books for Young People) is the most important source of information about global literature for children and young adults -- and it's always been a mystery to me why Singapore isn't a member (though I almost forgive them because of their annual Asian Festival of Children's Content (AFCC) which does so much to promote regional authors and illustrators). I moved to Thailand two years ago and was thrilled to be back in a country with an IBBY branch.

Bookbird journal (via Project Muse) - e.g., read this article by professor Kathy Short (think: Worlds of Words) based on a keynote she gave at the 2018 IBBY Congress in Athens: "The Dangers of Reading Globally."

Biennial congresses - the next one is in Moscow, 5-7 Sep 2020, and the one after that is Malaysia, 5-8 Sep 2022 (and I expect all our active Asian teacher-librarian networks to be fully contributing)

The Bologna Children's Book Fair, where every April countries converge in Italy to exhibit and exchange publishing rights, is strongly connected to IBBY -- and is a wonderful place to physically browse the best of children's books internationally. Next month is its sister event, the Shanghai Children's Book Fair, and I'm hoping some fellow teacher-librarians will be attending and passing on books to watch out for in translation.

I was lucky enough to be at the Bologna Children's Book Fair this past April when the winner of the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award was announced. When the crowd around me heard the name "Bart Moeyaert," it burst into wild cheers and clapping. But my colleague Philip Williams and I just looked at each other in embarrassment and said, "Who?" A quick search on our phones for books to immediately order revealed the disappointing news that no English translations of his work are still in print (though I trust the re-publishing wheels have started turning since then). Knowing about good authors and books is only half the battle.

In seeking books to put on a Red Dot shortlist, we have often come up against the problem of availability, e.g., does a translation exist?, is the book still in print?, and/or is it easy for our schools to order the book and get it delivered to Singapore?

Awards, no matter how small (like the Red Dot), create ripples of awareness. That's why we teacher-librarians watch each others' awards closely, looking for titles to read and potentially add to our own collections or shortlists, e.g.,

the Panda Awards in China

the Sakura Medal in Japan

the Golden Dragon Awards in Hong Kong

the Morning Calm Medal in Korea

the Bangkok Book Awards in Thailand

But it's frustrating if you can't easily get your hands on books from other countries.

For example, Nadine Bailey and I are both judges for the Neev Book Awards, a relatively new award looking for "high-quality children's literature from India" leading to "a fuller understanding of India, Indian lives, and Indian stories." This year the winning title in the Neev YA category is "Year of the Weeds" -- a book we passionately recommend -- and one which pairs perfectly with a former Red Dot title from Canada, "Blue Gold" -- as both highlight the human costs of mining metals to feed our appetites for the latest technology.

While the Canadian novel is readily available via sites like Amazon.com or Book Depository, the Indian one is not (yet). Yes, it is listed on the Amazon India website, but people outside of India can't use that (without a credit card registered to an address in India).

I know both Nadine and I will be advocating for "Year of the Weeds" to our colleagues on the Bangkok Book Awards and Panda Awards committees (the local ones we now serve on, having cut our teeth in Singapore on the Red Dot Book Awards). Getting copies will be tricky, but we're working on ways to help others get a chance to read this brilliantly humorous novel that offers an insightful critique of the abuses of democracy and capitalism through the lens of the Gond tribe, an indigenous people of India. (If you aren't familiar with the Gond, please seek out "The London Jungle Book" -- as you will never forget the arresting images and metaphors the author/illustrator employs to explain his culture in that picture book memoir.)

Following and participating in awards like the Red Dots is invaluable for those of us entrusted with expanding the arena of possible discovery for young people. As Dr. Edith Ackermann so eloquently expressed it, "We have a responsibility to introduce children to things they don't yet know they will love."

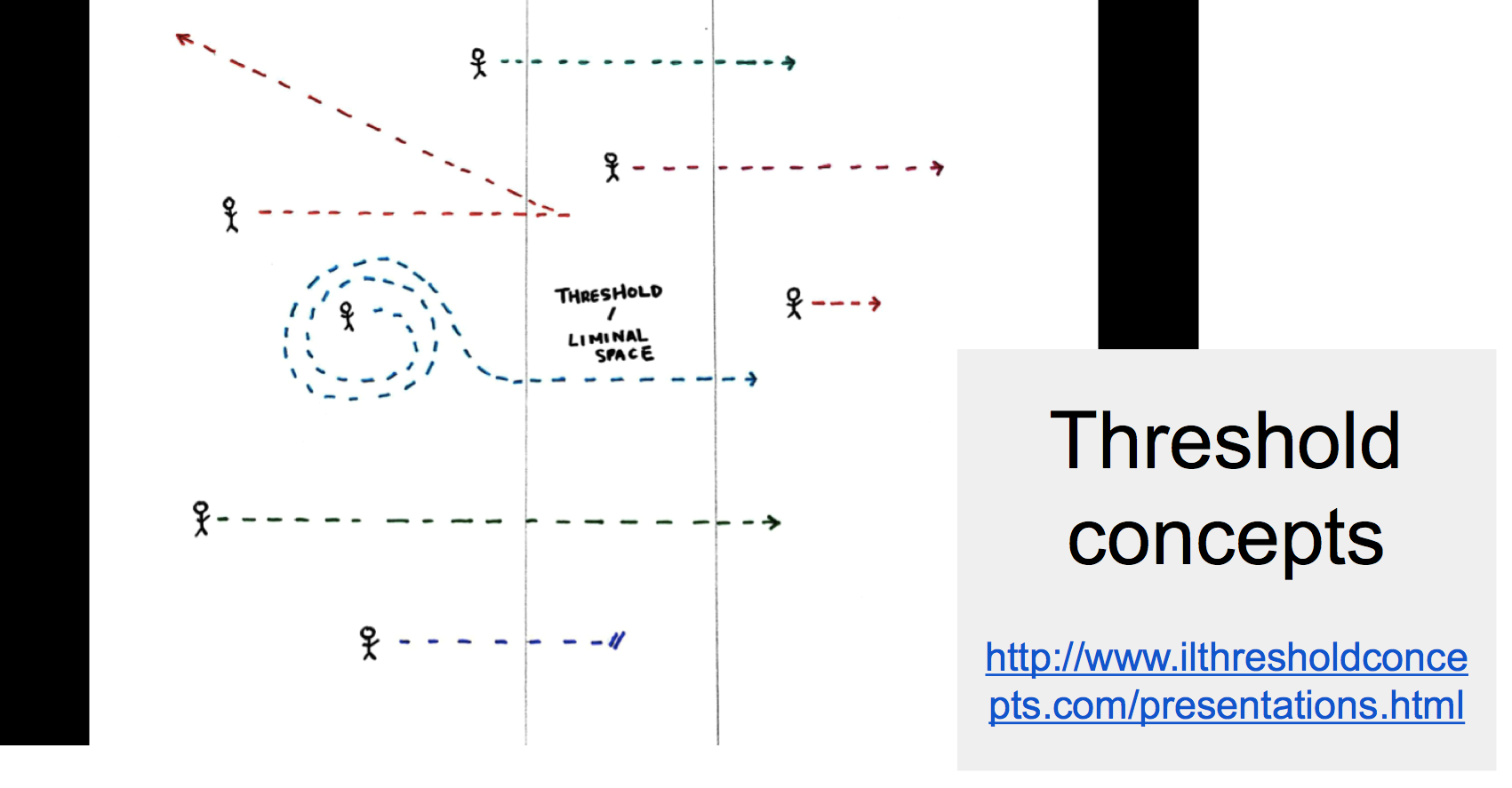

I view these annual award exercises as formative assessments, where the "canon" taught in our schools (or stored in our book cupboards) is the equivalent of summative assessments. We librarians can help those canons evolve by continuously exploring world literature in order to provide new, refreshing, mind-expanding reading material -- for our students and our teachers.