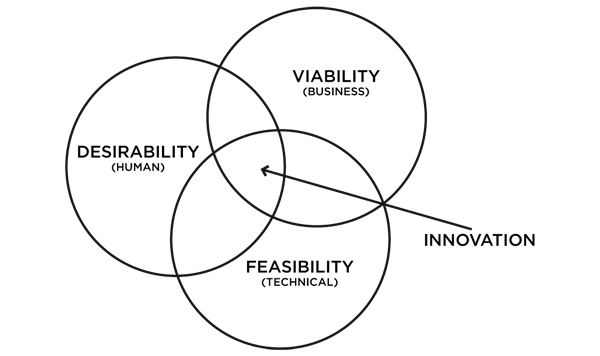

- What model do you use, if any, and how effective is it (conceptually and as a visual representation), given your curriculum and age group?

- Which phases of the inquiry do you find students have the most difficulty with? Are they skill-based problems? Or conceptual? Can you give examples?

- Which phases are easiest?

- Which concepts and/or skills do you think are the most important to teach for your age range?

- Any favorite strategies / mini-lessons / metaphors for teaching them?

- How is research/inquiry visible in your classroom? What are your favorite tools for making the process visible and/or assessing prior, formative, and summative knowledge, whether collective or individual?

- Any examples you can share of visualizations or evidence of inquiry?

- Are there any books you feel serve well as mentor texts for inquiry/research?

- What are your favorite resources relating to research/inquiry? (e.g., books, blogs, people, theories)

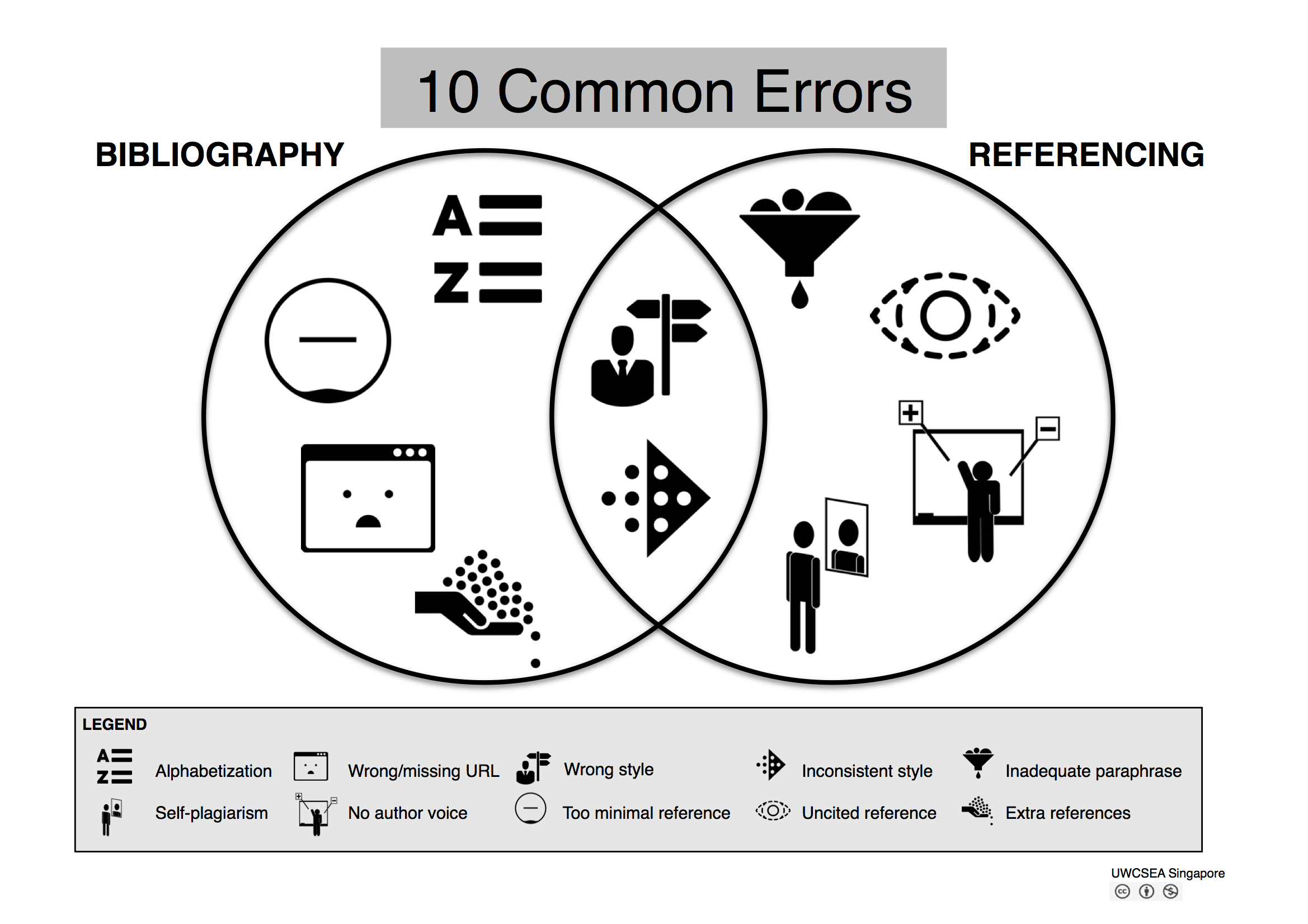

- What level of referencing do you think is reasonable for your age group?

Last month in Prague, I got the chance to dive deep with small groups of teacher-librarians on the concepts behind teaching research -- at the School Librarian Connection conference.

My preparation for the workshop began with a survey -- for both teachers and librarians* -- and those questions provided the basic outline of my half-day sessions (the morning one focused on primary school, the afternoon on secondary).

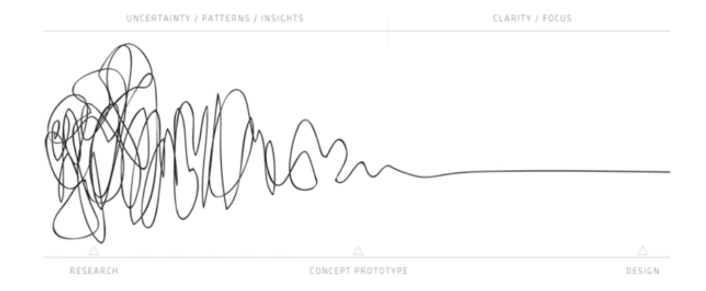

Research models are the most obvious visual place to start.

Workshop participants responded to some models highlighted in my slides in extended table discussions and then by hand annotations on a wall chart -- as the slides below show.

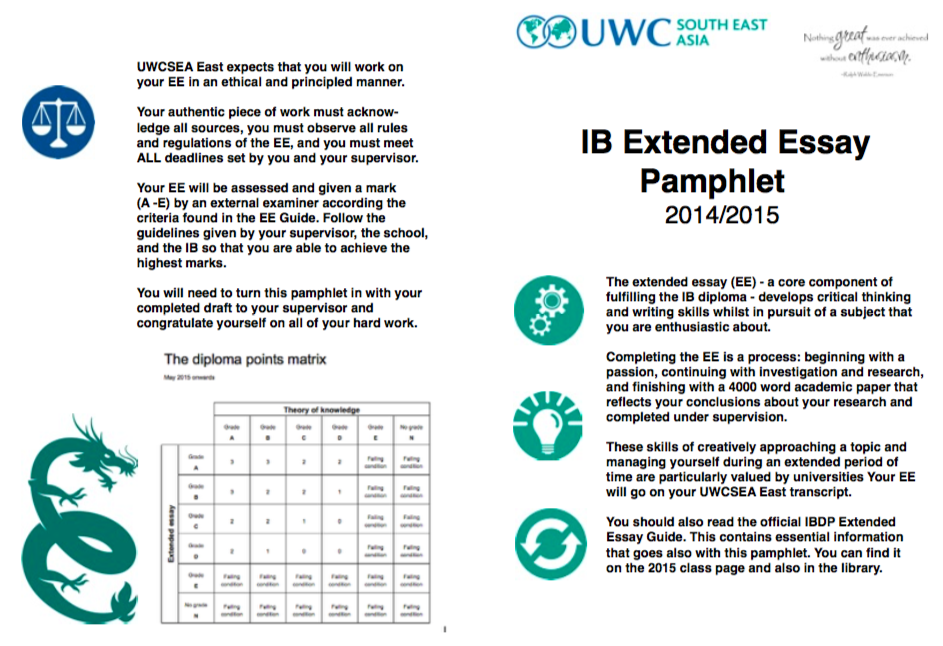

Of particular interest was the new (unpublished) UWCSEA East model, heavily influenced by two of our gurus: Kath Murdoch for inquiry, and Cathryn Berger Kaye for service learning (e.g., her MISO (Media / Interview / Survey / Observation) approach).

Kath does a lot of work with international schools, and I pointed out that both UWCSEA and our host, the International School of Prague, are thanked in the acknowledgements of her recent book, The Power of Inquiry. Only one other school was familiar with Cathryn Berger Kaye's work, but raved about her as an on-site presenter and consultant.

We then considered overall metaphors for research, e.g., the journey, and the difference between skills and concepts -- before mapping and discussing ones we felt were easier or harder for particular age groups.

The full set of slides from my presentation are below. I ended the session by running through some of my favorite metaphors related to research.