Books are powerful in so many ways. They contain the power to allow people to speak across time and space — and cultures. The voices and images that come out of books have the power to create “mirrors, windows, and doors” (as Rudine Bishop Sims, a giant in the field of children’s librarianship, once said). Mirrors to reflect identities, windows into other worlds, and sometimes sliding glass doors allowing readers to step into other realities.

But what worlds are contained in the books on offer at a school like ours? Is our collection balanced in terms mirrors, reflecting the range of our community, vs. windows, providing enough views of other worlds? What is enough? And what worlds aren’t being represented?

Books are products emerging from political, economic, and cultural systems, and this is especially true for children’s books, because societies tend to control what their children are told and taught. So it’s interesting to consider what messages manage to be written by whom, privileged by whom, published by whom, and distributed/promoted by whom. What messages aren’t being conveyed? Why or why not?

I think about these questions every day in some way, whether in choosing what book I should read next, or choosing books to order for our library, or trying to figure out how students absorb and interpret the books they read, while wondering what texts they really are reading — and why or why not?

My master’s degree in children’s literature (20 years ago) looked at the works of “A.L.O.E.” (A Lady of England) — a very privileged British woman who wrote books for children in both England and India — and even moved to India as a missionary, “to civilise the natives.” Christianity, not surprisingly, was a dominant ideology of her books, as it was of the British imperialist project. (You can read the whole thing here: “A.L.O.E.: Writing Home”. Good material for insomniacs.)

Not surprisingly, since that time I have maintained a particular interest in children’s literature emerging from India. I get to read a lot of it these days, as I’m part of a judging panel for the Neev Book Awards — for outstanding children’s literature which “leads to a fuller understanding of India, Indian lives, and Indian stories.”

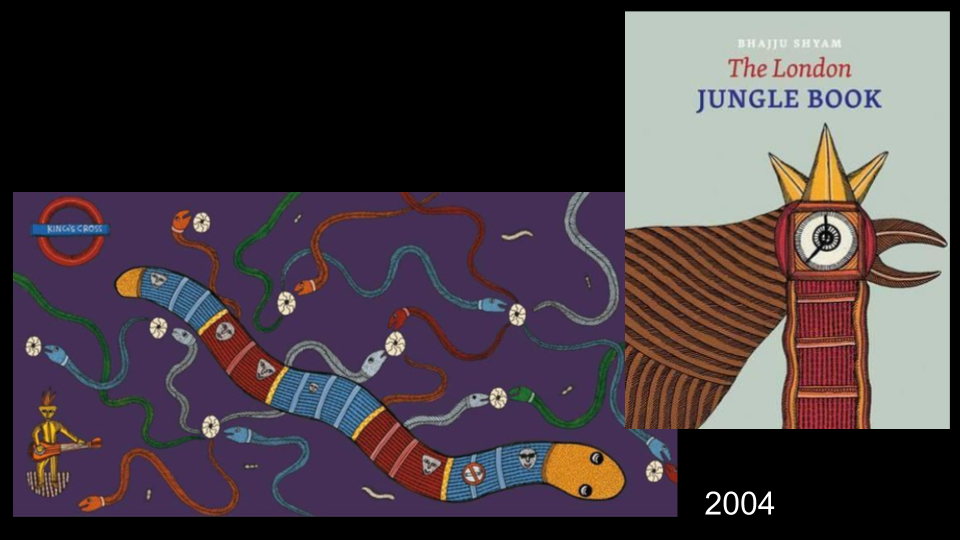

My favourite book (for children and adults) that exemplifies global understanding is “The London Jungle Book” by Bhajju Shyam, which narrates the experience of a man from one world traveling to another for the first time (including first time on a plane), expressing his perception of the other’s world using his own culture’s art. The book is a diary of an artist from the Gond tribe in central India who moves to London, England, to work for two months. He just nails British culture in a visual and insightful way that I, as an American who lived in London for many years, could never have done. I am so grateful for his voice — and as a librarian, it is a privilege for me to share voices like his, ones that don’t always get heard. (I also wonder what A.L.O.E. (whose real name was Charlotte Maria Tucker) would think as she read it….)

That book was published by my favourite Indian publisher, Tara Books. A year ago I attended an international school librarian conference in Chennai, India, where Tara Books is located — and got to visit both their production workshop and main storefront. See photos here. Notice how the artwork in the books is being silk-screened. The books are handmade, which is something that begs a question. In how many countries would this be possible? How much do we pay for these books? How much are the workers remunerated? What are the economics behind the international flow of books around the world? Tara Books is unusual, but this kind of an exception makes you think hard about the rules.

Looking ahead, I’m so excited that a Tara author — who also happens to have attended NIST for several years as a student! — is coming in June to be the graduation speaker for the class of 2019. Amazingly, Samhita Arni became an author when she was in her teens, having written a re-telling of the great Mahabharatha when she was 12. More recently, Tara Books has published Samhita Arni’s version of the Ramayana from Sita’s point of view — a female perspective on power, privilege, and male politics. Last November Arni published an article in an Indian newspaper, highlighting the resilience of Sita in making her own choices and the importance of “small acts of rebellion.”

It is because of stories like these that I long ago became hooked on books and then began to use my own power and privilege as a librarian, with the economic and political means to spread textual products (read: books), to encourage multiple voices and other worlds to be explored.